A Novel That Parses the Inexplicable

This piece appeared in The Wall Street Journal on September 11, 2011

A NOVEL THAT PARSES THE INEXPLICABLE by DANNY HEITMAN

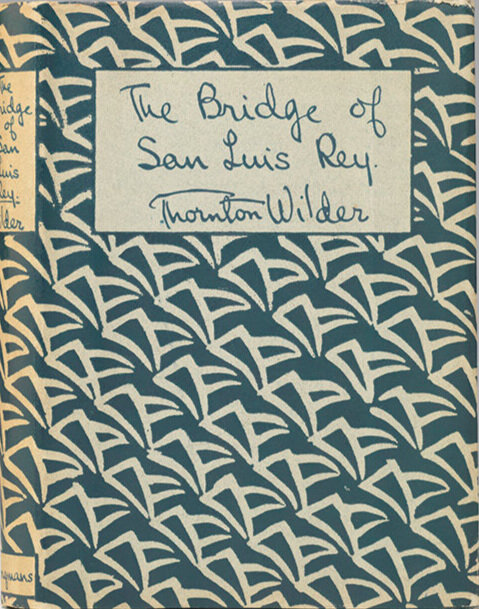

This initial first British edition of The Bridge of San Luis Rey by Longmans, Green (1927) was called the “preliminary issue” because it preceded both the first American edition and the first British edition by a few days. The special printing consisted of just 21 copies.

This weekend, America marks the 10th anniversary of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. In our continuing efforts to understand and come to terms with the deadliest assault on U.S. soil, "The Bridge of San Luis Rey," Thornton Wilder's 1927 novel about the cruelties of fate and the redemptive power of love, still resonates with renewed urgency.

As novelist Russell Banks notes in his introduction to a 2004 edition of the book, "We are the only species that does not know its own nature naturally and with each new generation has to be shown it anew," adding that, "It is interesting, therefore, and possibly useful to consider this novel in the long and (at the time of this writing) still darkening shadow of the terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington, D.C."

Mr. Wilder's novel chronicles the fictional collapse, in 1714, of "the finest bridge in all Peru" and explores how the seemingly random deaths of five travelers on it at the time prompt their neighbors to question the basic patterns of existence.

Writing the book between two world wars, Mr. Wilder is quick to point out that the fickle hand of death is an all-too-common theme of human experience. He has the novel's narrator wonder why the great bridge's demise and the resulting loss of life should surprise anyone:

"Yet it was rather strange that this event should have so impressed the Limeans, for in that country those catastrophes which lawyers shockingly call the 'acts of God' were more than usually frequent. Tidal waves were continually washing away cities; earthquakes arrived every week and towers fell upon good men and women all the time. Diseases were forever flitting in and out of the provinces and old age carried away some of the most admirable citizens. That is why it was so surprising that the Peruvians should have been especially touched by the rent in the bridge of San Luis Rey."

However, the singular power of "The Bridge of San Luis Rey" derives from Mr. Wilder's ability to see such tragedies with a fresh sense of awe. He frames this vision in the very first sentence, with what appears to be a spare, dispassionate recitation of the basic facts: "On Friday noon, July the twentieth, 1714, the finest bridge in all Peru broke and precipitated five travelers into the gulf below." But in citing the time, Mr. Wilder alludes to our tendency to fix on the precise moment of such tragedies, such as the oft-repeated facts that the first of the Twin Towers collapsed at 9:59 a.m., and the second at 10:28 a.m. It is almost as if we feel that by measuring the manic sweep of such calamities with a watch, we can gain some control over an event that seems not a creature of time but a break in time itself.

Mr. Wilder also notes how deceptively tenuous the solid texture of our daily landscape can be: "The bridge seemed to be among the things that last forever; it was unthinkable that it should break. The moment a Peruvian heard of the accident he signed himself and made a mental calculation as to how recently he had crossed by it and how soon he had intended crossing by it again. People wandered about in a trance-like state, muttering; they had the hallucination of seeing themselves falling into a gulf."

Equally compelling is the novel's grasp of the spiritual stock-taking that follows large-scale disasters, manmade or otherwise. The story's narrator discloses that in the aftermath of the bridge's collapse, "there was great searching of hearts in the beautiful city of Lima. Servant girls returned bracelets which they had stolen from their mistresses, and usurers harangued their wives angrily, in defense of usury."

The largest exercise in soul-searching, however, and the one that forms the novel's core, is undertaken by the zealous cleric Brother Juniper. He witnesses the bridge collapse and confronts the central spiritual question of this event and others like it: "Either we live by accident and die by accident, or we live by plan and die by plan."

Juniper begins researching the lives of the bridge's five victims, hoping to puzzle out the mystery of why these people—and only these people—were singled out for such a dramatic demise. His quest becomes an obsession, as he fills notebook after notebook with details about the victims, creating a magnum opus that attempts to explain the mind of God using logical formulas. "It seemed to Brother Juniper that it was high time for theology to take its place among the exact sciences and he had long intended putting it there," readers learn.

Juniper's manuscript is an intellectual Tower of Babel, a conceited enterprise that is destined to fall as conclusively as the bridge itself. The cleric's project eventually incurs the wrath of the community, which seems like the rough justice of a fool getting his due. But he inspires sympathy, because in his quest for a reassuring context and narrative for the disaster, we see ourselves.

If Juniper's ambition to tie up all the loose ends in the aftermath of tragedy proves futile, what are we to glean from such happenings?

Mr. Wilder concludes "The Bridge of San Luis Rey" with the suggestion that in the face of overwhelming human loss, people should take comfort in the love that binds the living and the dead, regardless of the cold machinations of fate—a lesson that can seem at once profound and prosaic. Perhaps anticipating his critics, he says at one point in his novel that "there are times when it requires a high courage to speak the banal."

Mr. Wilder's conclusion didn't seem banal to British Prime Minister Tony Blair. In the aftermath of Sept. 11, Mr. Blair chose to honor the British victims of the attacks by quoting from the final passage of "The Bridge of San Luis Rey": "There is a land of the living and a land of the dead and the bridge is love, the only survival, the only meaning."

Mr. Heitman, a columnist for The Baton Rouge Advocate, is the author of "A Summer of Birds: John James Audubon at Oakley House" (LSU Press, 2008).